| SOCO Blog |

17 April 2015

SKY CATS

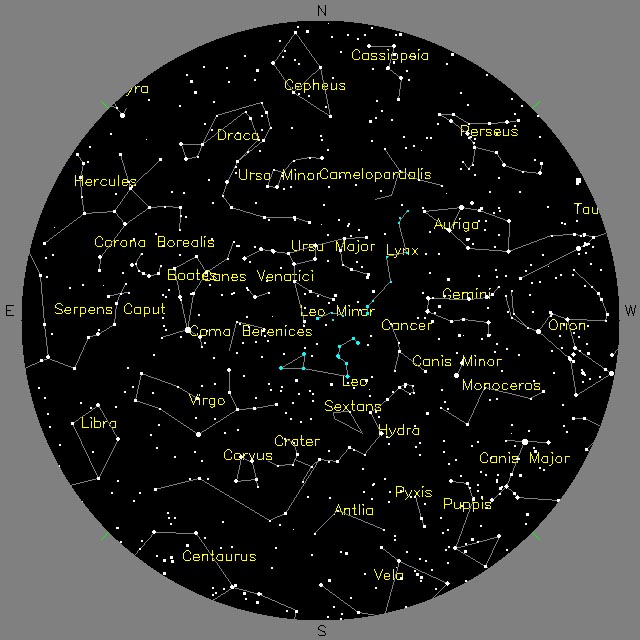

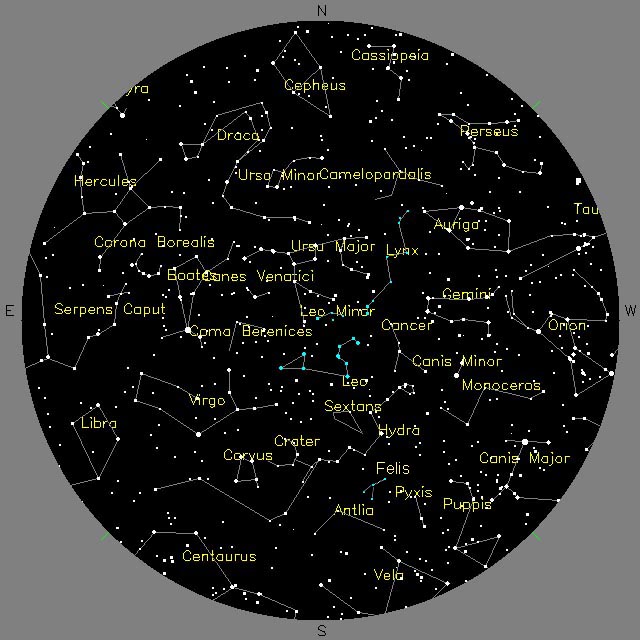

Spring is the time of nature's re-awakening when animals come out of their lethargy to roam their territories with renewed vigor. My cats, who spent the winter cold spells curled up sleeping in the house, have now responded to their instinctive urges and prowl the surrounding landscape in search of potential prey (mostly mice). However, spring is the time not only for earthly cats to prowl, but also cats of the celestial nature. There are three modern constellations that depict cats and, either by design or coincidence, they all occupy the central region of the sky this time of year. As shown in Figure 1, the stars of these constellations— Leo, Leo Minor, and Lynx— are directly overhead a few hours after sunset in mid-April.

Figure 1. Star chart for the SOCO site in mid-April at around 11:00 pm CDT. Stars of Leo, Leo Minor, and Lynx are highlighted in blue.

Source: Your Sky Website.

Most people are familiar with Leo, the lion, because it is one of the signs of the Zodiac. The bluish first-magnitude star at the heart of the lion— Regulus— culminates (reaches its highest point in the sky) at around 10:30 pm in mid-April. Incidently, the star in the Cat-Star logo represents Regulus (it is the "cat star"). While Leo is a grand and easily seen constellation, the adjacent Leo Minor (the Lesser Lion) is a poor collection of dim stars that goes unnoticed in our modern light-polluted skies. The same is true for Lynx (the Lynx). Lynx is a relatively recent constellation, created by Johannes Hevelius in the 17th Century from some faint stars lying between Ursa Major and Auriga. It is said that he gave the constellation its name because it's stars are so dim, it takes a "lynx-eyed" person (i.e., a person with exceptional eyesight) to be able to see it.

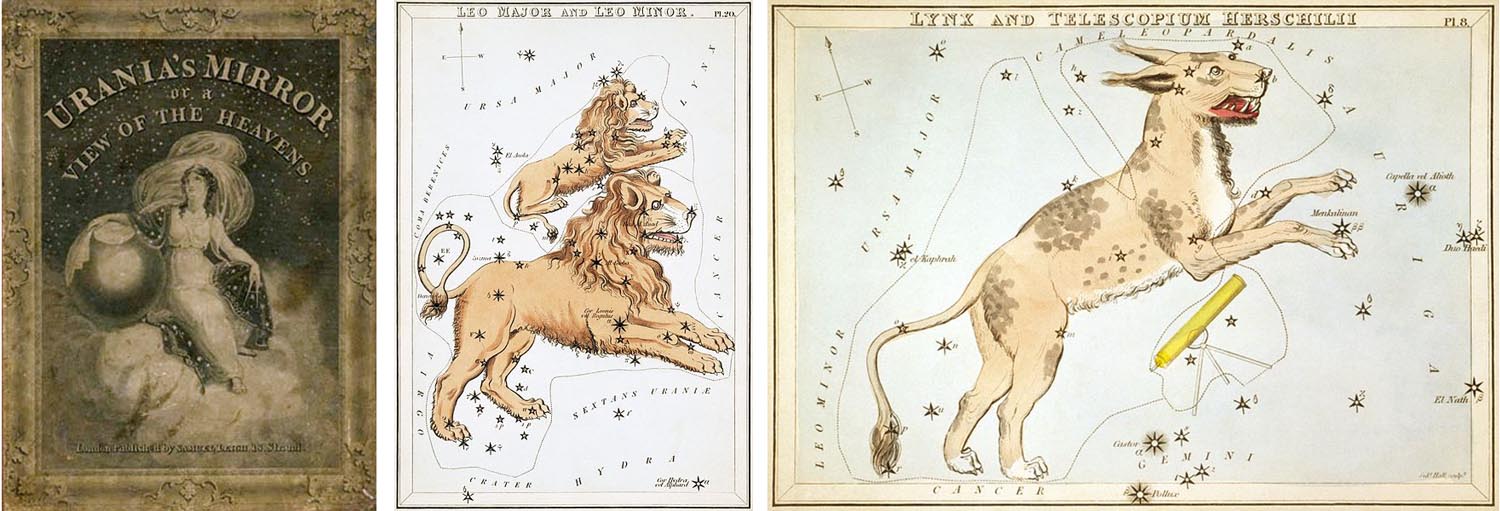

For the classical depictions of these constellations, I turn to a remarkable source that I have recently come across. This is the stunningly beautiful Urania's Mirror, which was published in England in 1824 as a boxed set of 32 astronomical star charts printed on cards. In addition to engravings of the constellations, the cards had holes punched in the locations of the major stars so that, when a card was held up to a light, the stars were illuminated. The illustration on the box lid, which depicts Urania (the goddess of the night sky and the muse for all astronomers), is shown in Figure 2 along with the cards showing Leo, Leo Minor, and Lynx. A gallery of all the cards can be found on Wikipedia.

Figure 2. Box lid illustration for Urania's Mirror (left) and the cards for Leo, Leo Minor, and Lynx.

As might be expected for publications from its era, the illustrations of animals in Urania's Mirror are not always entirely accurate. I'm struck by the representation of Leo Minor as sort of a midget adult lion next to the full-size lion of Leo. Why not depict the Lesser Lion as a smaller young lion? And the engraver obviously never had a close look at a real lynx! He got the tufted ears correct, but the head and body of the creature looks more like a dog. And lynx don't have long tails. Still, the illustrations in this card set are beautiful and take us back to a time long before the Internet when gentlemen and ladies amused themselves in English parlors with educational devices such as this.

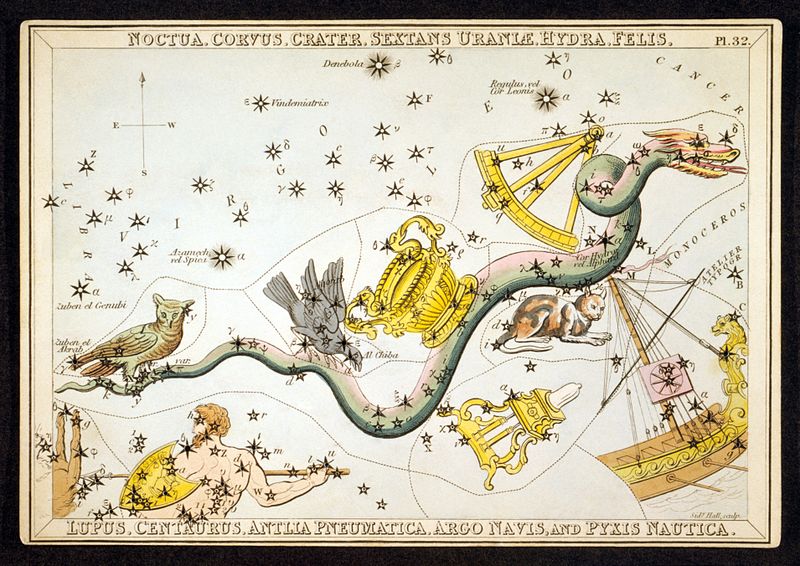

In addition to the three current "sky cats", there once was another cat prowling the heavens. The French astronomer Joseph Jerome de Francois Lalande, a colleauge and friend of Charles Messier, was very fond of cats. So, in 1799 he created a constellation using some dim stars lying between the existing constellations of Hydra and Antlia and called it "Felis" the cat. As described by Ian Ridpath in his Star Tales website, Lalande convinced the Prussian Johann Elert Bode (somewhat of a rival of Messier's in terms of astronomical discoveries) to include Felis in the 1801 edition of his star atlas Uranographia. An illustration of Felis from Bode's atlas is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The constellation Felis as it appeared in a color version of Bode's Uranographia.

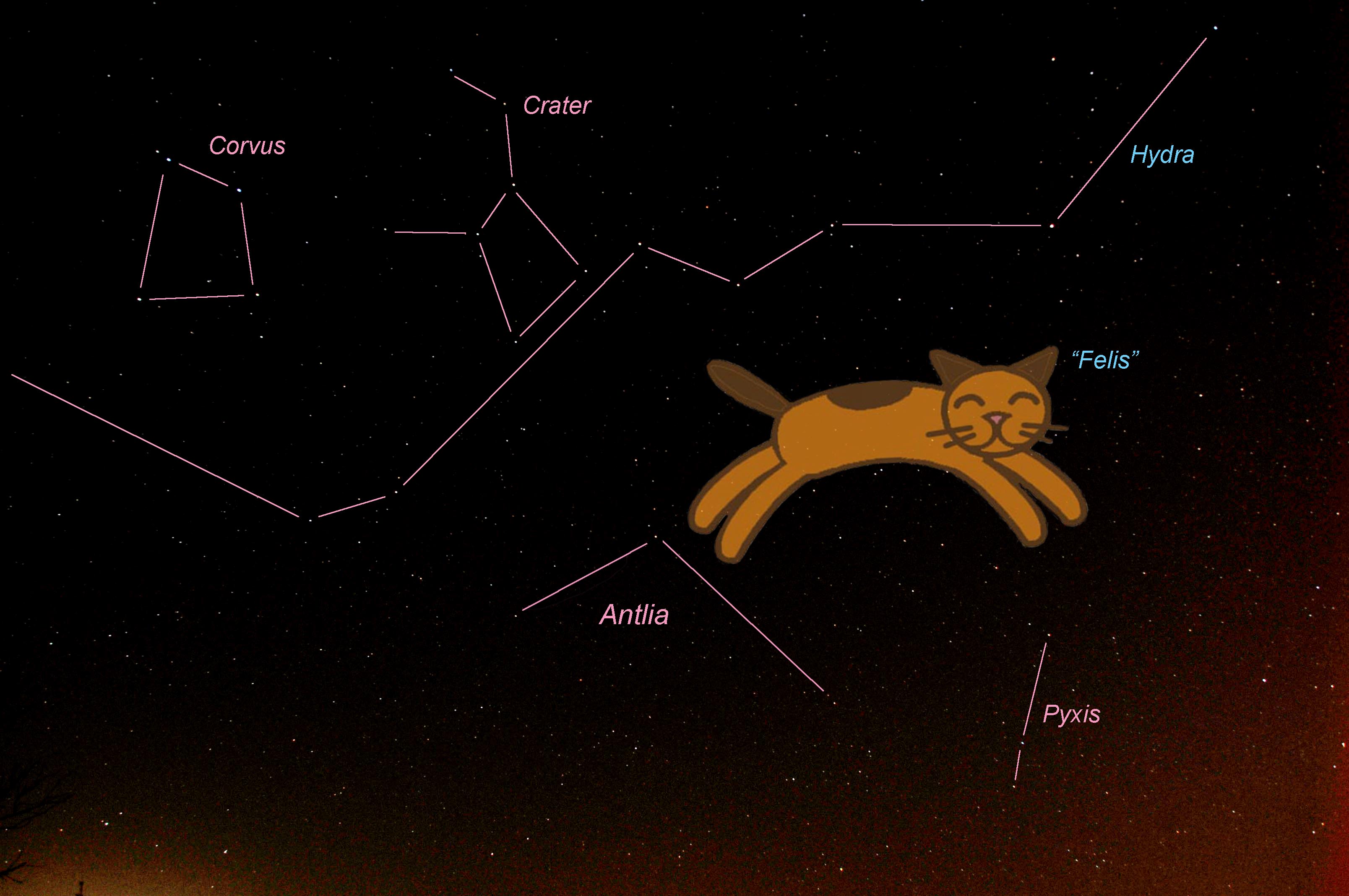

Referring to the chart in Figure 1, we can see that Felis occupied the same general part of the sky as the three other "sky cats", using the space between the current constellations of Hydra, Antlia and Pyxis. Felis appeared in a few other sources, including the planisphere of Angelo Secchi in 1878 (where it had the Italian name "Gatto"). And, notably, it appeared on one of the cards in the Urania's Mirror set, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Felis as it appeared in Card #32 of Urania's Mirror, along with neighboring constellations.

Alas, while the stars are "permanent" in the sky, constellations come and go. Eighty years after its introduction by Lalande, Felis and other constellations included in Bode's star atlas (like the "Brandenburg Scepter," "Frederick's Honor," and the "Mural Quadrant") were abandoned by other chart makers. I think this is kind of sad. I'd rather have a constellation that is a cat than a constellation that is an air pump (Antlia). I mean, really— an air pump?

So, since Felis is sort of an abandoned cat, maybe we should adopt him. Figure 5 shows a 15-second image of the southern sky just above the horizon taken a few days ago (the reddish glow of light pollution is visible along the lower margin) using a Nikon D300 camera with an 18-200 mm AF-S Nikkor lens, mounted on a tripod. Yes, there are no really bright stars in this region of the sky, although the "box" of Corvus stands out reasonably well in the upper left corner. Figure 6 shows the constellations in Figure 5, along with the location of Felis according to the old star charts. Comparing Figures 5 and 6, there are a few dim stars that could make up this constellation. None are readily visible to the naked eye but remember that, in the days of Lalande and Bode, the night sky was a lot darker (even in the cities). The constellation of Felis probably was recognizable under those conditions. So, maybe the situation is really that Felis is still there in the heavens, but we just can't see him now. Accordingly, I've revised the star chart from Figure 1 to include Felis among the other "sky cats" prowling the spring sky (Figure 7).

Figure 5. Image of the sky above the southern horizon containing the stars of Felis.

Figure 6. Image from Figure 5 showing the constellations, including Felis.

Figure 7. The star chart from Figure 1 revised to include Felis.

Today, with our technology that includes go-to telescope mounts that slew automatically to the correct Right Ascension and Delination of an astronomical object, constellations are little more than trivia. However, for much of the history of astronomy, constellations were very important— the constellation within which an object (like a planet or comet) was observed could mean whether a country would go to war, or if the leader of a new religion was being born. The fact that we "see" patterns in the stars is a testament to the power of our imagination. Constellations today are not essential to astronomy, but they're still fun.

|

Return to SOCO Blog Page

Return to SOCO Blog Page

Return to SOCO Main Page

Return to SOCO Main Page

Questions or comments? Email SOCO@cat-star.org